|

THE ORIGINAL ARTICLE

To which this has all been a

supplement!

From the May/June, 1992 issue of Muzzleloader Magazine

"What name has he gained by his

deeds?"

"We call him Hawkeye," Uncas

replied, using the Delaware phrase; "for his sight never fails. The Mingos

know him better by the death he gives their warriors; with them he is 'The Long

Rifle.' "

-James Fenimore Cooper, The Last of the Mohicans

All around me I could hear the

pitiful moaning, painful cries and desperate screams for relief that pierced the

darkness. Blood, thick with dirt, grit and matter, littered my comer of the

compound. Everywhere I beheld British

regulars, tired women and lost children all ripped asunder by cannon shot and

mortar rounds. The early morning darkness enveloped Fort. William Henry. Fog

crept over the wooden walls, moved slowly along the ramparts and overflowed into

the compound in a gray, opaque cascade. The smoke of a dozen or more burning

fires twisted skyward above the red, orange and white flames that hungrily

devoured the barracks, the east wall and the stored grain.

From underneath the southeast rampart,

surrounded by the bitter stench of putrid flesh, I watched in silence as the

coot fog mixed with the warm smoke. Not too far from my false shelter, a

bloated, bay horse lay prostrate, entangled amongst the leather reins, wooden

tongue and busted wheels of a smashed and burning supply wagon. The rampart

immediately above me intermittently shook, dropping dust, wood slivers and mud

daubing down upon the lowly huddle of King George's good citizens. Between the

screams, the cannon rounds and the desperate shouts of command, I heard the

crying of an abandoned baby.

Through the momentary flash of an

exploding shell, I spotted an infant, naked, reaching for some unseen hope and

kicking at misunderstood danger. The toddler's blond hair fell matted and

crusted across his forehead. His mother sat crumpled against a wooden barrel,

one limp arm holding the child close. A com husk doll, splattered in red and

brown, stood erect within the folds of the mother's ragged skirt.

I tried to run a wad of tow up

and down my rifle barrel, using the occasional mortar flashes and the popping

fires as my only light. Sweat soaked my hunting shirt, stung my eyes and dripped

off my chin. I stumbled in the choking smoke with the tow worm, standing hunched over the muzzle of my rifle to keep the

falling debris out of the rifle bore. After swabbing the bore of my rifle, I

crouched down to cover the flash pan with my body. As I did I glanced to my left

and saw that someone had taken the baby away from his dead mother. Although the

child had disappeared, his crying kept drumming in my brain. Through the cannon

fire, the shouts and screams and the explosions, I kept hearing the child's

agony. I could not escape the nightmare of that terrified boy, who looked much

like my youngest son. But my son was safe with his mother back on our homestead

south of Lake George.

Did that unknown child have anyone left

who would hear his cries and understand the loss? As I stood up and prepared to

run across the compound, I could hear the crying once again. This time, though,

the pain seemed new, all the more intense and afraid. I followed the sound of

that child, moving toward the darkened corner of my sheltered hideaway. I

stepped over one soldier whose taxed breathing wheezed slowly from a hole in the

man's throat. One hand grabbed my buckskin legging, his only good eye searching

my face while his lips moved in mute animation. The poor soul wanted something

that I could not give. Nearby I helped a dazed camp follower lift her man to his

feet.

Once again the child's crying beckoned

me. While searching the darkened comer under the rampart and next to the sally

port, I came across a private I had once known as a friend. David Duncan,

originally from Birmingham, full of good jokes and funny stories, now sat there

against the wall and simply stared at nothing. Just then another cannon round

hit the rampart directly above me, sending the dirt, splintered wood and debris

crashing heavily around us. The concussion slammed me to the earth. With my arms

I covered my head, choking on the dust and smoke. When the dust settled, I could

no longer hear the crying. The child had disappeared along with the one-eyed

private and my forlorn friend. Instead, only a black, jumbled hole remained.

One of my neighbors, big William, found

me in the rubble and pulled me to my feet. I balanced myself on my rifle and

wiped the blood from my left ear. William propped me against one of the pillars

adjacent to the sally port opening and yelled something to me, but I couldn't

hear him. I do remember looking down at my rifle and noticing that mud and straw

caked the muzzle and the hammer was gone.

As I steadied myself against the

pillar, I saw the sally port entrance suddenly illuminated by a blaze of torch

light. The warring seemed to cease for one brief moment while a half dozen

Highlanders came marching up the sally port. They held their torches high,

causing the flames to billow across the ceiling and down the sides of the

tunnel. With solid steps of determination, the Scotsmen marched out of the hole

and past me, never looking to the right or left. Behind them came a ragged party

of two women, plus a young British lieutenant, who all appeared out of their

element. Although the trio's dress was ragged, filthy and soaking wet, it was

obvious that the New York frontier was not their home. Their silver-spoon

upbringing had surely tarnished under the black soil of the hardwood forest, but

whoever they were, they must have been important, because the Highlanders

watched them closely.

Gradually the numbness within my head

was giving way to a low humming between my ears, and while I massaged my

forehead with my hands, I witnessed another tired but seasoned group emerge out

of the darkness of the sally port. I knew that we finally had some real hope in

the midst of that awful night, because not too far behind those misplaced gentry

approached my old friend Hawkeye and his Indian brothers Chingachgook and Uncas.

I had last seen them at Cameron's cabin during John

Cameron's summer celebration. We were

all so happy that day, so relaxed in the wan-nth of friendship, feasting and

enjoying woodsmen's games. But that day was an eternity from the dismal

existence of Fort William Henry under siege. At the sight of those three, and

especially Hawkeye, I unconsciously smiled, forgetting for a brief moment the

hopelessness of our situation....

"Cut!"

"Cut! Cut!"

"Cut! Cut! Cut!"

"That's a print!"

"But, everyone back to their marks! Now!"

Within a brief second, the outdoor set

of the movie The Last of the Mohicans, located on the shores of Lake

James, North Carolina, changed from a state of magic to a hubbub of controlled

energy and confusion.

"Good," I confessed to Bill,

my fellow extra. "I'm glad for this break in filming. After fifteen,

sixteen takes of this same scene, my imagination was beginning to get the best

of me. I was beginning to think that I was really in the battle."

Bill and I continued talking quietly as

Daniel Day Lewis, Madeleine Stowe, Russell Means and the rest shuffled past our

leaning post, returning to their marks deep within the sally port tunnel. More

than 350 extras were also backtracking to their original spots, preparing once

again to run, shoot, shout and die on cue. The electrical crew silently drifted

from one lighting station to another, holding up their exposure meters and

calmly calling out directions to an unseen "Danny." Hair and makeup

personnel made their way through the crowds, spraying water on various actors'

hair, checking "burns" and "scars," and generally touching

up the various camera-front people.

The wardrobe folks with their pins, cloth measures and Velcro tape watched

for any opportunities to patch or mend Canada to be involved in the movie.

breeches, shirts, leggings or moccasins. The weapons master, Mark Hughes, and

the armorer, Vernon Crowfoot, along with other props people walked along the

ramparts whispering safety rules, knapping flints and rationing to the extras

their next round of paper cartridges. The set dresser, with his pump sprayer

filled with compressed burnt umber pigment, re-tinted any set areas that

reflected unwanted glare from the flood lights.

The craft services crew hustled amongst the actors, extras, crew and

production staff offering water, fruit drinks, soda pop, occasional snacks and

small conversation. The sound mixer constantly sat at his portable table hidden

behind a wall or perhaps a pile of sandbags and listened intently for speed

boats, flying aircraft, automobiles or any thing else that might contaminate the

desired 18th century sound. The wranglers guided and pulled the horses, goats

and oxen away from potential danger and back to their pre-determined positions.

Above the nighttime bustling throughout the fort, most people could hear Dale

Dye barking a few orders to his "troops," reminding the British

soldiers who they were, what their places were in this world and just what they,

as grunts, amounted to during this whole operation. His haranguing worked rather

well, for after several tiring weeks of daytime ambushing and Albany marching,

followed by four straight weeks of all-night siege fighting, his collection of

reenactors, romantics, unemployables, ex-hippies and rock-n-rollers performed

with the best of military precision.

Hundreds of Native Americans, coming

from as far away as Montana, Oklahoma and Canada, moved among the soldiers and

civilians throughout the set pretending to be Mohawks, Hurons, Abenakis and

"French Indians." Every day before filming began each Indian underwent

an elaborate routine of applying tattoos and makeup and hair styling. The tattoo

crew and the makeup personnel carried metal rings attached at their waists from

which hung Polaroid shots of each Indian character's specific look. By referring

to the proper photo, every Indian had his tattoos re- y airbrush and stencil,

then his hair styled appropriately. Throughout this colossal effort to duplicate

a fraction of literary vision loomed the camera boom, which silently rough and

above the fort interior. A Steadicam operator, a camera unit weighing more than

100 pounds, rested takes, preparing once again to walk backwards, up a through a

tunnel while trying to capture the best graphic moments. Everywhere the

Steadicam operator sound man followed guiding a microphone held aloft by a

twenty-foot aluminum shaft. Outside the walls and several stories over the North

Carolina forest hung a light platform that ended from a monstrous yellow crane.

Secured within the sat an unfortunate lighting technician who took s via a

two-way radio. He spent his nights pretending to be the moon.

Every night this entire collage of

color, sound, personas and emotions centered on just two individuals: the film's

director and executive producer Michael Mann, whose vision and energy brought

Cooper's story back to the big screen; and assistant director Michael Waxman.

Mann finalized each scene as he walked about the set. He did not say much,

remaining focused and spending his energy imagining, planning and thinking. On

the other hand, Waxman constantly chewed on plastic straws and listened intently

to Mann, being forever prepared to relay Mann's wishes energetically through the

elaborate radio system. Both men balanced well each other's temperaments,

causing the wonderful tale of America's first fictional hero to emerge from

potential mishap.

Through these two men, "Quiet on

the set ... Sound ... Action!" signaled the beginning of the biggest

production I have ever witnessed. And for seven straight weeks, I had the an

opportunity to make-believe that I hope to never forget. Although I have come to

appreciate the difference between Hollywood's image of Colonial frontiersmen and

the actual characters who trekked the virgin hardwoods, I must admit that movies

and certain television scene influenced my early interest in muzzleloading firearms.

; an adult I still enjoy historically based movies. Although two-dimensional

images conveyed through celluloid are largely make-believe, they are

nevertheless eternally fun to , especially ones set in America's Colonial era.

When I got an unexpected phone call

from Julie Kobrinsky, researcher for Forward Pass Productions, who asked me some

provocative questions, well, I couldn't help but wonder if my pilgrim's journey

was about to come full circle. Julie quizzed me about woodsmen running through

the woods while reloading their rifles. She also asked about secrets of

reloading quickly but in a traditional, "authentic" manner. I tried to

explain to her on the phone how it can be done, but I also emphasized that these

routines were inherently dangerous and at best should be explained in person.

Julie replied that they had all of the technical advisors they needed but

thanked me for my time, saying that they would "be in touch."

Oh well. But a phone call like this one was a brand new experience for me, so

I naturally shared the story with a close friend of mine. I contacted Tom Allen

as soon as I got off the phone with Forward Pass Productions. Tom suggested that

I send Hollywood a video of me "in action," running and reloading,

plus standing and shooting repeatedly at a single mark. My chance to be in front

of the camera was easier than I thought!

The next day, equipped with a video

camera, tripod and an instant film crew of loyal friends, we all headed for

Blacksmith Fork Canyon to shoot a scene "on location." We spent the

afternoon playing Hollywood, filming our own version of a woodsman shooting from

behind a tree, then re-loading while running from make-believe foes and finally

shooting again before exiting camera right. The first shot, the running and then

the second shot took all of 42 seconds of film but hours to plan, rehearse and

tape. We then filmed two scenes of a linen-and- leather-clad woodsman shooting,

as fast as possible, in a two- minute segment.

The mini-movie worked. The very day

Hollywood received the overnight package, Forward Pass Productions called me.

That one video, along with my curriculum vitae and a few color stills,

nudged me down the path that eventually led me full circle in my pilgrim's

journey. In the following months, I reviewed the script for the supervising

producer, tried to get my woodsmen friends noticed by the casting department and

generally enjoyed but did not always understand the ride that propelled me to Ashville,

North Carolina.

Initially, my responsibility fell to

training Daniel Day Lewis, who was playing Hawkeye, to run while reloading

Killdeer. That responsibility, though, quickly spread into other previously

unrealized duties. Rifle-maker Wayne Watson of Leonardtown, Maryland, had built Killdeer

and did a superb job in trying to balance authentic styling with Michael Mann's

vision of what the mythical longrifle should took like. But on the morning of

Lewis' first training session, the rifle had never been shot by anyone on

location. As a result I had the privilege of working out a live load for the

rifle and coaching Lewis at sighting in his mainstay.

I was to meet Lewis' physical trainer

at the downtown Asheville production offices at 9 a.m. on Monday. From there the

trainer took me by car to the city's chic health spa where the powers

responsible had calculated that Lewis would soon be returning from his morning

run of several miles. As we were approaching the spa, sure enough, there he was

running at a fast pace down the street while clad in blue spandex tights, a

loose, red athletic shirt and long raven-black hair that would make most

woodsmen jealous.

The plan called for Lewis to get in a

morning's worth of running, followed by a strenuous aerobic and strength weight-

training program. While he lifted, I busied myself in my own weight-training

routine. While trying to focus on weight-training, I studied Lewis, watching him

take his workout very seriously. I had heard previously that he was an ardent

long-distance runner and a superb athlete, but that morning spent running and

weight- training gave me an opportunity to see firsthand the hard work Lewis was

going through to "be" Hawkeye.

After Lewis' workout, which lasted

about three hours, we left the spa in a pristine 1950 Ford Pickup, and he took

me to lunch at the "Cafe on the Comer." We talked about the movie, his

goals in interpreting the role and how that included using Killdeer as the rifle

would have been used over 250 years ago. I found the actor to be very polite and

sincere, even humble. As reflected in his passion to excel physically, he was

just as driven to properly interpret Cooper's hero, Hawkeye. While we munched on

fresh greens, sliced avocados and grilled chicken, we shared our ideas about

Colonial woodsmen and their rifles. Just behind Lewis I could see an attractive

woman continually whispering to her friend and pointing at our table. Somehow I

knew she was not referring to me.

Once lunch was over, I gathered up what

the Hollywood crew called my "kit," consisting of my rifle, shooting

accoutrements, leggings, breechclout and moccasins, and climbed into the back

seat of the Lincoln Town Car that Lewis' personal chauffeur had already parked

in front of the cafe. With Lewis in the front seat next to the driver and myself

sharing the back seat with Killdeer, we headed south of Asheville, as the

timetable mandated, to the fire fighter's training grounds.

Driving down the secluded dirt road leading to the cleared fields and covered picnic

area that constituted the training grounds, I was beginning to enjoy

"living the part," but a period trek had never quite been like this.

As our car approached the first grassy field, I could see scores of fresh

recruits marching and drilling under the demanding cadence of the

military-technical adviser, Date Dye, and the military-extra coordinator, Dale

Fetzer. I knew that in that crowd were several of my friends, who by then had

been marching, standing and drilling according to the manual of arms for several

hours under the hot, North Carolina sun. They were surely fatigued and covered

in sweat. While the car slowly cruised along the dirt road and the stereo

projected soft tunes, I lowered the tinted electric window and scanned the rows

of soldiers. I could not help but smile and wave at Tom Phillips, Tony Gerard,

David Bonesteel and the rest of the soldiers who had spent the better part of

that hot day doing what soldiers do.

We cruised on down to the shady side of the meadow and then parked the

Lincoln by a grove of tall hardwoods. While we sipped chilled, imported spring

water and listened to the distant shouting of a British army in motion, Lewis

and I changed into our 18th century clothing.

We spent the rest of the afternoon working up a good load, sighting in

Killdeer and then devoting a considerable amount of time practicing the art of

simultaneously running and reloading. Besides being a durable athlete, Daniel

Day Lewis is also a superb marksman. While shooting at a two-liter pop bottle,

he had the feel of Killdeer mastered after just three rounds. The plastic

container was filled with water, and on his third shot, Lewis clipped off the

neck of the bottle, leaving the rest of the container undisturbed. And yes, that

was where he had aimed the rifle.

Next we practiced the routine of running while reloading. Repeatedly, we

trotted along the meadow's edge, pouring powder, ramming a wad, priming the pan

and getting off the next shot. Lewis soon grew confident in reloading on the run

and wanted to do the same while firing a live round. In the interest of blending

safety and historical accuracy, we started the run with a clean, empty bore.

Lewis moved along the trail at a quick clip, dumping powder while counting to

five, removing a round ball from his mouth and placing it in the bore of Killdeer,

ramming the ball home and finally priming with the big horn. After one afternoon

of practice, he could get such a shot off-and hit the mark-in less than 30

seconds.

After spending two afternoons training with Lewis, I developed a fond

appreciation for the frontier image that Michael Mann had envisioned and Daniel

Day Lewis was intent on maturing. To run down a trail while keeping abreast of

Lewis offered a unique glimpse of the next Hawkeye. I could watch closely as he

used his teeth to remove the plug from the horn and smoothly worked the ramrod

into the muzzle, doing all with the look of Hawkeye on his face and his long hair blowing

out behind him. To me the whole exercise was truly an N.C. Wyeth painting in

motion.

For the most part, that is how my summer of "moviemaking"

.progressed. Simply put, I had a ball. Working on The Last of the Mohicans was

undoubtedly the best summer job I have ever endured. But after seven weeks of

mostly all-night shooting, I was physically drained. I could fall asleep

anywhere, in any position and had lost approximately ten pounds. The weeks of

standing, waiting, rehearsing and trying to guide hundreds of Colonial extras

through the art of dressing and acting "in character" proved

unbelievably taxing.

But the physical drain was worth it to be able to experience just how a

colossal, $40 million movie project like 20th Century Fox's The Last of the

Mohicans is accomplished. Especially when working on location. First of all,

the unusually wet season of that North Carolina summer continually forced delays

in the filming schedule. In addition, the tasks of working out the logistics of

moving the support facilities; of providing for the hundreds of crew, cast and

production people; and of organizing the feeding of sometimes 700 people during

a single day's shooting all seemed nearly impossible.

Then there was the wardrobe department. The tailors and seamstresses were

responsible for designing, getting approved and amassing the clothing needed for

hundreds of Colonials, soldiers, Indians and principal characters. That included

fitting each actor, silent bit player and featured extra as well as scores of

background extras.

The wardrobe department needed thousands of center-seam moccasins for the

Indians and the Colonials. To overcome this obstacle, they developed a

center-seam moccasin top made of deerskin that could be sewn together quickly

and hot-glued to a black, cotton Chinese slip-on shoe. In order for the

principal actors' moccasins to withstand the abuse of an action-packed shooting

schedule, each pair designed for them was made from the same moccasin tops but

was glued to state-of-the-art running shoes. On camera, however, one will be

hard put to notice any "artificial" moccasins.

Supplying leather leggings that looked like brain-tanned deerskin involved

similar innovation. Originally, actual brain- tanned deerskin was the

preference, but the logistics of acquiring the projected amount proved

unmanageable, so the wardrobe people again went to work. They produced their

"brain-tanned" deerskin by first bleaching chrome-tanned deerskin,

then stretching each skin in a frame and sandblasting both sides. After sewing

up each set of leggings, they were then patted with different colored earthen

pigments. The end result produced a legging that I found hard to differentiate

by touch or look from an actual brain-tanned deerskin legging except that such

leggings were uncomfortably warm during an August afternoon in North Carolina.

Scores of British and regimental uniforms were constructed out of pure wool,

closely matching the actual colors and cut of the original French and Indian War

uniforms. When different British regiments were needed from one day to the next,

during the night and into the morning the facings of each coat were removed or

covered up with the required color.

And since the 18th century would not be complete without wigs, hundreds of

human-hair wigs were delicately crafted in the production warehouses located in

downtown Asheville. Each wig used in the movie was hand-sewn by professional wig

makers from British Opera circles. Each hairpiece involved a painstaking ritual

of using a single needle and thread to bind a strand of human hair to a cloth

skull cap. Over and over the process was repeated until a full or partial head

of brown, black, gray or white hair finally evolved.

Someone paid a lot of attention to Hawkeye's wardrobe. Besides an ample head

of hair on the hero, he also wore a plain pullover (or wraparound) hunting shirt

of the proper length, a woven sash, a breech clout, sideseam leggings and

moccasins. His waist sash was always tied in back, alluding to Joseph

Doddridge's original description of a woodsman's basic attire. Besides his

legendary Killdeer, Hawkeye also sported a hand- forged belt knife that rode

securely in a quilted knife sheath. Both his powder horn and shooting bag rode

just below the hollow of his ribs, hanging in a workable and believable

position. His powder horn strap was constructed of deer sinew and actual wampum,

and Lewis insisted on using and carrying the same accoutrements in his shooting

bag that woodsmen commonly toted.

Every small arm fired during the

various scenes in the movie were charged with black powder originally dispensed

in hand- made paper cartridges. Every gun fired was an actual flintlock. Some

were even original weapons of the early to mid-18th century. As an example,

during the course of my tenure with The Mohicans, I carried a 1730 Charleville

musket, an immaculate, short Jaeger of the same period, plus a hefty

transitional rifle made especially for this movie. During one rain delay, Vernon

Crowfoot allowed me to cruise the armory trailer and try the feel of Scottish

cutlasses, Scottish pistols, French trade guns and English fowlers, all of which

were from the 18th century.

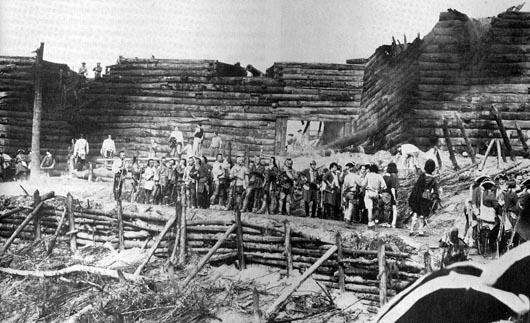

The fort sight was an outstanding feat

in location design. From the shores

of "Lake George" to the surgeon's quarters, massive efforts in

detailing the grounds to look like the Colonial frontier were evident. The huge skeleton of a

burned-out, wooden ship was first made in Asheville and then moved to the lake's

edge. Electrically fired, fiberglass-constructed siege cannons and sturdy

mortars defended the fort's walls and armed the French trenches. Hand-crafted

gabions, fascines and Cheveaux de Frize littered the charred, eroded, pulverized

battlefield. Even the bottles, wooden kegs, wagons, eating utensils and

surgeon's tools looked as if they were recently robbed from a museum.

Enjoying the opportunities afforded me last summer, I was able to move

through the props, wardrobe, special effects, casting and production

departments. I witnessed Michael Mann's vision of Cooper's tale coming to life

from a thousand different angles and am happy I was there. I am thankful the

project was completed, and so that black powder buffs may be able to see more

movies made in a similar setting, I hope for the movie's success at the box

office.

I have long since left the North Carolina hills and returned to my everyday

world, but some questions still remain with me. I will always wonder why

green-to-the-woods locals were used instead of seasoned woodsmen reenactors,

especially when I knew of 30 or so who were willing to come for the filming. Of

the 50 or more Colonial extras I trained and supervised, only two had ever

previously fired a black powder weapon, let alone trekked through the woods. And

I know that if moviegoers look hard enough, they will certainly see modem

eyesores flash across the big screen. I also know that Michael Mann's vision is

different than the original 1936 black-and-white movie starring Randolph Scott,

and it is certainly altered from Cooper's original tale. But I am glad the tale

has been told once again.

Hawkeye is worth remembering

|