|

MENUS! STOREFRONTS! Guide book STILL Available - Free Downloads Only! In COLOR! |

|

|

|

|

|

![]()

![]()

A large force of British regulars tramps down an old Indian

trail which serves as their roadway. Resplendent in their bright red uniforms

and polished steel accoutrements, they provide a rich visual counterpoint to the lush

greenery of the surrounding virgin forest. Accompanying this arm of the Crown

are many colonial militia, women, sutlers, and the like. But for the tramping

of feet, the jangle of equipment, the songs of the birds ... there is silence.

A large force of British regulars tramps down an old Indian

trail which serves as their roadway. Resplendent in their bright red uniforms

and polished steel accoutrements, they provide a rich visual counterpoint to the lush

greenery of the surrounding virgin forest. Accompanying this arm of the Crown

are many colonial militia, women, sutlers, and the like. But for the tramping

of feet, the jangle of equipment, the songs of the birds ... there is silence.

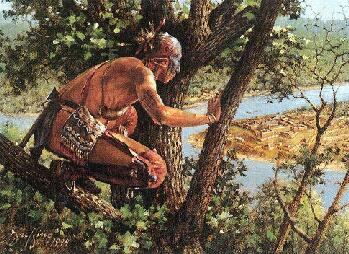

Robert Griffing painting

Suddenly, near the rear of the column, a small band of Indian warriors emerges from the darkness of the woods. They cut down several of the British. They disappear. A grenadier company - the cream of each British regiment - forms up and fires at a nearly invisible enemy. The march resumes. There is firing upon the right flank. A party of Rangers & Indian allies pursues the unseen foe into the forest. To no avail. Confusion & panic begins to permeate the ranks ...

Seemingly, the above description is right out of Michael Mann's The Last of the Mohicans, and its depiction of the Fort William Henry massacre. But is it? Fast forward to ...

Hidden in the forest within the depths of the trees, and on both sides, are hundreds of Indian warriors. They begin a fusillade of fire which tears into its increasingly terrified targets. The British fire blindly. As comrades fall, and their attempts of their own defense prove futile, panic spreads. Troops huddle in a mass, desperately attempting to reach the safety of the center. Gunfire, women's shrieks, smoke, war whoops ... it all equals death to the bewildered British. All sense of order is lost. Officers desperately attempt rally, or even orderly retreat. It is useless. Warriors swoop upon the mass. Proud British might has been reduced to rubble in the unfamiliar confines of the wilderness ...

Still think we're speaking of The Last of the Mohicans? It is easy to see why. These two portions of our account of an historical event, though separated in time by 3 days, very closely approximate the filmmakers' vision of the Fort William Henry massacre. [Please see our FORT WILLIAM HENRY ... The Siege & Massacre for the true story!] In some respects, as pointed out in our On the Trail of the Last of the

Mohicans guide booklet, it resembles James Fenimore Cooper's version, largely based on the panic-stricken refugees' early reports of the affair ... people like Jonathan Carver of Massachusetts. Yet, it isn't. It precedes the Fort William Henry siege by two years. It does not occur in the colony of New York, but rather in that of the Penn's Woods, Pennsylvania, in the early stages of the great French and Indian War.

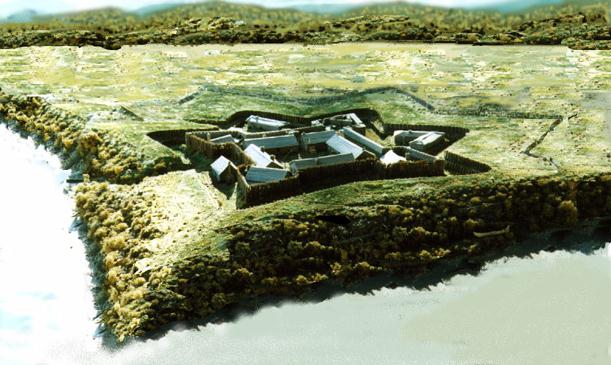

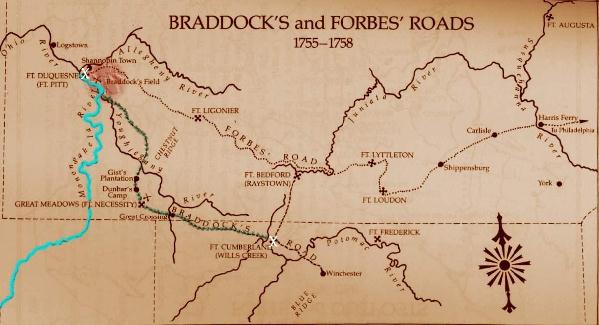

Call it what you will, the Battle of the Wilderness, the Battle of the Monongahela, or simply Braddock's Defeat, as it is popularly known, it is very much not any scene from The Last of the Mohicans. It centers not around Fort William Henry, guarding the passage way of the Lake George/Lake Champlain corridor, but rather about a great French fortress, Fort Duquesne, standing guard at the confluence of two mighty rivers, the Allegheny and the Monongahela - joining forces to form one grand river way, the Ohio. It was a critical juncture in the frontier. Holding this point meant control of the Ohio River Valley and the fur trade & Indian alliances that came with it.

View of Fort Duquesne as it must have looked in 1755 ...

Diorama photo courtesy of Table Top Studios

Chains of forts sprouted up around the frontier extending the lines of communication from New York to Fort William Henry, from Quebec to Fort Duquesne. Each little garrison became an isolated outpost serving not only as frontier guardians, but as supply depots and campaign launching points. Thus, destruction of links in these communication lines severely hampered, if not crippled, operations of the enemy. So it was that Major General Edward Braddock, then 60 years old, led an expedition against the French strategic stronghold, Fort Duquesne. Though well versed in military tactics, Braddock had never before led troops in battle. Carrying huge siege cannon with him, this didn't figure to be much of a battle anyway. The fort would fall.

The French, too, knew this. They had neither the manpower or supplies to survive an extended siege by the British firepower being lugged their way from Maryland's Fort Cumberland, over 100 miles of wilderness away. Duquesne, very near the location of a previous, short-lived, structure originally constructed by the British, before being driven off by superior French forces and rebuilt, would be only the first to fall, for surely a domino effect would occur throughout the region. The other forts were smaller in size and garrison. It was simple. To maintain dominance in the area, to strengthen alliances with the native population, Duquesne could not be allowed to fall.

Manning the fort was a recently swollen garrison of some 600 or more French & Canadians, with plenty of artillery in its massive bastions. Yet, it was readily accepted that it could not stand against the columns of British now known to be creeping, ever so slowly, their way ... numbers that were falsely reported to be as high as 4,000 men. So it was that a body of men comprised of 36 officers, 72 Regulars, 146 Canadian militiamen, and 637 Indians, from the assorted allied tribes of Hurons, Potawotomis, Ottawas, Shawnees, Missisaugas, Iroquois, Delaware, and Mingos, all under the command of Captain Daniel-Hyacinthe-Marie Lienard de Beaujeu, were dispatched from Duquesne on the morning of July 9, 1755 rushing to intercept the approaching British as they were fording the Monongahela at one of two crossings. For reasons not fully known, they were late. The British crossed both fords, in force, unmolested.

The column of British meandering their way through unfamiliar wilderness to lay siege to Fort Duquesne read like a who's who of Colonial British America - George Croghan, Horatio Gates, Robert Orme, Sir John St. Clair, George Washington, Thomas Gage, Daniel Boone. These, and others, made their uncertain way through the forest with Braddock. They lugged both field and siege cannon, as well as a train of supply wagons, further slowing the progress. All in all, perhaps 1600 men were in the field, consisting of 2 Regiments of British regulars, the 44th, under the command of Colonel Sir Peter Halket, and the 48th, commanded by Colonel Thomas Dunbar. Accompanying these regiments were 200 sutlers, wagoners, and other armed "hands," a group of volunteers, 40-50 women, and a few Oneida Indian allies. One private in the group bore the name - a wonderful LOTM tie-in - of Duncan Cameron.

Let's back up three days earlier, to July 6, 1755. This is the day skirmishing took place that is described in the opening paragraph above. This was the first contact between the opposing forces of this campaign, and when Fort Duquesne commander Captain Claude Pierre Pecaudy, sieur de Contrecoeur, first learned of the presence, in the immediate area, of this rather large British assemblage. Awed by the display of artillery, it was decided to attack the force on the move, rather than await their arrival at the fort. The next two days passed without incident. The 7th was spent by Braddock's men excruciatingly slowly skirting some swampland. On the 8th, they passed through a 3 mile long valley, with heavily wooded hills on both sides. It appeared a perfect ambush place, and Braddock had the heights scoured by flanking parties. Nothing happened.

Dawn came on the 9th of July. It wasn't till sometime after 9AM that Captain Beaujeu's mixed French and Indian force left Duquesne. By that time, Braddock was crossing the fords. By noon, it was completed. They were safely across the Monongahela. Braddock had expected an ambush the day prior, back in the valley. It never came. Surely, the French wouldn't miss another opportunity. Yet, again, no ambush was forthcoming during a time of British vulnerability. Braddock and his officers decided that it must be that there was to be no ambush. Obviously, the French had decided to make a stand at the fort. Braddock's force was now about a mile from the river.

It was a complete and utter surprise ... for both sides! It was an accidental

collision in the woods. The English now had a false sense of security. The

French were still intent on a crossing ambush and were rushing, pell- mell, to

the fords. Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Gage led a vanguard force of some 300. They

rounded a bend in the narrow road, with a rise of land to their right. Scouts

came rushing back with the news. The French were just ahead. The French force,

taken equally by surprise at the appearance of the scouts, opened fire. Gage

ordered his force into line and they fired several volleys in the finest

European tradition. At a distance of about 200 yards, it was mostly a futile

display. At least one ball, however, found its mark. French commander Beaujeu

fell dead. Momentary disarray permeated the French body, but it didn't last long

as second in command, Captain Jean-Daniel Dumas, quickly rallied his men. The

Indians streamed down both flanks, under cover of the forest, took aim from

behind trees, and raked the British with enfilade fire. The French regulars took

position across the road to the front, most probably in a pre-dug trench. [If there was a trench, it was obviously not dug on

the spot. Perhaps, a French work party had dug it, in the days immediately preceding,

to delay British siege supplies on the "road."] It was

described as a massacre.

It was a complete and utter surprise ... for both sides! It was an accidental

collision in the woods. The English now had a false sense of security. The

French were still intent on a crossing ambush and were rushing, pell- mell, to

the fords. Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Gage led a vanguard force of some 300. They

rounded a bend in the narrow road, with a rise of land to their right. Scouts

came rushing back with the news. The French were just ahead. The French force,

taken equally by surprise at the appearance of the scouts, opened fire. Gage

ordered his force into line and they fired several volleys in the finest

European tradition. At a distance of about 200 yards, it was mostly a futile

display. At least one ball, however, found its mark. French commander Beaujeu

fell dead. Momentary disarray permeated the French body, but it didn't last long

as second in command, Captain Jean-Daniel Dumas, quickly rallied his men. The

Indians streamed down both flanks, under cover of the forest, took aim from

behind trees, and raked the British with enfilade fire. The French regulars took

position across the road to the front, most probably in a pre-dug trench. [If there was a trench, it was obviously not dug on

the spot. Perhaps, a French work party had dug it, in the days immediately preceding,

to delay British siege supplies on the "road."] It was

described as a massacre.

The French had deployed in a crescent shape and were virtually unseen. From the forest, from the trench, and from the rise of ground, they poured down lead on the British advance party. The besieged began to give way. Gage attempted an orderly withdrawal, but lagging behind, was a work party, still advancing. The retreat crashed into the advance, adding further to the confusion. It was only 15 minutes into the battle and a fifth, or more, of Braddock's army was in utter disarray.

It got worse. The baggage train followed the work party. The seething mass of terrified men, mingling almost aimlessly, now had whatever hope of escape they might have had blocked by their own supplies. Officers desperately tried to maintain order throughout the battle. The chaos was becoming uncontrollable. The horses of the train began to feel the panic. They, too, became uncontrollable. The war whoops of warriors added to the surreal atmosphere of death and destruction.

Meanwhile, Braddock, with his staff, including George Washington, and the

bulk of the army, having finished the fording of the Monongahela, heard what

they at first thought was skirmishing up ahead. As the nature of the seriousness

of the affair became apparent, Braddock led the bulk of troops forward to join

the fray. For the second time, a collision occurred on the narrow pathway. As

the mingled and mangled vanguard, work party, and baggage train attempted

desperate withdrawal, their comrades rushed forward to their aid. Two forces of

equal momentum bearing down on one another. All the while, the French and Indian

crescent spread out, and after an hour's time, had about completely engulfed the

army of Braddock.

Four times, Braddock had his horse shot out from under him. His officers bravely urged the men to stand. Many officers were shot down by their own rebellious troops. Instead, they huddled. They attempted to burrow to the center. It was slaughter for the British regulars. At one point, 2 6-pounders, that had accompanied the vanguard, were turned against them upon capture by the French. Many of the American militiamen reverted to forest warfare and attempted resistance. Mistaken for Indians, some were killed by their own allies, the British regulars ... what relative few were actually returning fire. For two more hours the British attempted to cut their way out of the trap. In vain, a meager attempt was made to seize the rise of ground. It failed.

Deterioration continued, despite the best efforts of Braddock. Mortally wounded, he still attempted rally. The envelopment continued. It was close to becoming a complete encirclement from which there would be no escape. The wagoners, et al, most prominent of whom may have been Daniel Boone and Daniel Morgan, were gone. They had chosen to live to fight another day. Most, if not all, organized resistance ceased to exist. The body of men, those surviving, finally, after enduring 3 hours of hot lead, hideous screams, and death all around them, broke and fled through the opening to the rear not yet closed off by the French. Casualties were horrific. Nearly all the officers and about two-thirds of the fighting men were dead or wounded. Of Braddock's staff, only Washington was alive and relatively well. The rout was complete. Left in its wake, were artillery, guns, ammunition, wagons laden with supplies, horses, cattle, Braddock's papers & personal effects, a chest of gold, and dead men ... perhaps 500 of them. Pursuers caught the stragglers, captured them, tortured them, killed them. The carnage reached all the way back to the Monongahela River crossing. There, it was abandoned. Pillaging the dead and wounded became the order of the day.

Back at Fort Duquesne, a prisoner whose life was spared, recalled this, a final snippet from right out of The Last of the Mohicans:

After sundown, I beheld a small party coming in with about a dozen prisoners, striped naked, with their hands tied behind their backs, and their faces and parts of their bodies blackened; these prisoners they burned to death on the bank of the Allegheny river, opposite to the fort. I stood on the fort wall until I beheld them begin to burn one of these men; they had him tied to a stake, and kept touching him with firebrands, red-hot irons, &c., and he screamed ...: the Indians, in the mean-time, yelling like infernal spirits.

And what of Duncan Cameron, the private? He survived, and his eye-witness testimony adds much to our present day interpretation of the event. He says, simply, of the aftermath: At Night when the Coast was clear, I got me out of my Hiding-place.

|

One Reliable Estimate of the Casualties |

|||

| ENGAGED | TOTAL | KILLED | WOUNDED |

| BRADDOCK | |||

| Officers & Staff | 96 | 26 | 36 |

| Troops, etc. | 1373 | 430 | 484 |

| BEAUJEU | |||

| French | 200 | 8 | - |

| Indians | 600 | 20 | - |

It was a shocking debacle. A superior force was nearly annihilated by an enemy barely half its size. The repercussions, though temporary, were tremendous. The French maintained exclusive control of the forks of the Ohio and the all important Ohio Valley. They had demonstrated their might by crushing a more numerous foe, convincing the united tribes of whom to call Father. Fort Duquesne stood proudly still.

One more thing. Had the fort fallen in 1755, it is very conceivable that Fort Niagara would have followed suit and the French, abandoned early on by their Indian allies, rolled up back into Canada. Very possibly, the siege at Fort William Henry might never have happened. There very well may never have been a The Last of the Mohicans tale to tell!

Point State Park - the site of Fort Duquesne in

present day Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

|

GETTING THERE! |

|

Point State Park, a National Historic Landmark, is at the tip of Pittsburgh's Golden Triangle. The 36-acre park is accessible from the east and west by I-376 and I-279, from the north by PA Route 8, and from the south by PA Route 51. In 1758, Fort Pitt was built on the site of Fort Duquesne after the retreating French burned it in the face of superior approaching forces. One of the three restored bastions now houses a museum, the Fort Pitt Museum, which details the history of that era. |

On the retreat to safety, General Braddock

succumbed to his wounds a few days after the Battle.

Along the Braddock, or Wilderness, Road [above, with monument on the rise to the

left], he rests to this day!

![]()

When the Forest Ran Red

~ purchase through this link helps to keep us afloat! ~

Return to the FRENCH & INDIAN WAR IN PENNSYLVANIA HOT SPOT MAP

Next In The History Series: BATTLE OF BUSHY RUN

![]()

![]() Copyright © 1997 - 2021 by

Mohican Press - ALL

RIGHTS RESERVED - Use of material elsewhere - including text, images, and

effects - without our expressed, written permission, constitutes copyright

infringement! Personal use on your own home PC is permissible!

Copyright © 1997 - 2021 by

Mohican Press - ALL

RIGHTS RESERVED - Use of material elsewhere - including text, images, and

effects - without our expressed, written permission, constitutes copyright

infringement! Personal use on your own home PC is permissible!

|

|